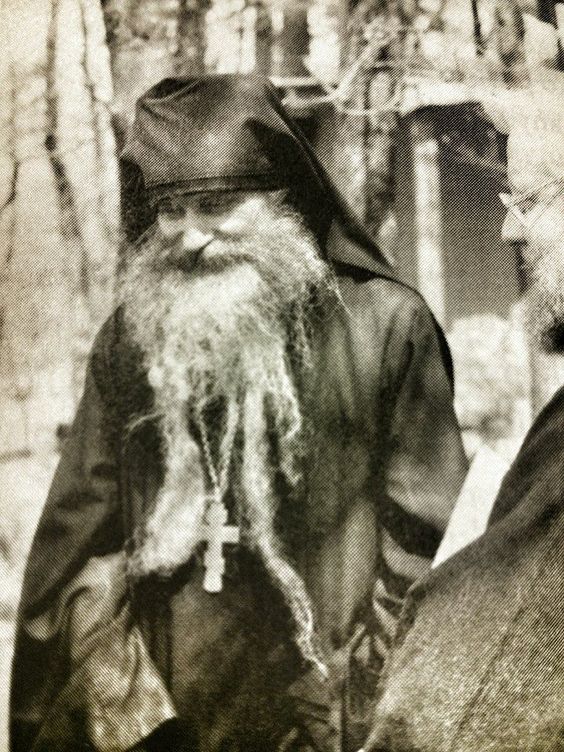

P. Seraphim Rose di Platina

tratto da: The Orthodox Word, vol. 11, n. 1 (gennaio-febbraio 1975), p. 35-41.

I Santi Padri della Spiritualità Ortodossa

Parte II. Come leggere i Santi Padri

LA PRESENTE PATROLOGIA prenderà in esame i Padri della spiritualità ortodossa; pertanto, il suo scopo e i suoi fini sono piuttosto diversi dal corso ordinario di Patrologia nel seminario. Il nostro scopo in queste pagine sarà duplice:

- Presentare il fondamento teologico ortodosso della vita spirituale: la natura e l’obiettivo della lotta spirituale, la visione patristica della natura umana, il carattere dell’attività della grazia divina e dello sforzo umano, ecc. .;

- e dare l’insegnamento pratico su come vivere questa vita spirituale ortodossa, con una caratterizzazione degli stati spirituali, sia buoni che cattivi, che si possono incontrare o attraversare nella lotta spirituale. Pertanto, le questioni strettamente dogmatiche riguardanti la natura di Dio, la Santissima Trinità, l’Incarnazione del Figlio di Dio, la processione dello Spirito Santo e simili, saranno toccati solo quando questi riguardano questioni di vita spirituale; e molti Santi Padri i cui scritti trattano principalmente di queste questioni dogmatiche e che toccano solo secondariamente questioni di vita spirituale, per così dire, non verranno discussi affatto. In una parola, questo sarà principalmente uno studio dei Padri della Filocalia, quella raccolta di scritti spirituali ortodossi che fu composta agli albori dell’età contemporanea, poco prima dello scoppio della feroce Rivoluzione in Francia, i cui effetti finali stiamo assistendo ai nostri giorni di dominio ateo e anarchia.

Nel secolo attuale c’è stato un notevole aumento di interesse per la Filocalia e i suoi Santi Padri. In particolare, i Padri più recenti come San Simeone il Nuovo Teologo, San Gregorio il Sinaita e San Gregorio Palamas, hanno cominciato ad essere studiati e alcuni dei loro scritti sono stati tradotti e stampati in inglese e in altre lingue occidentali. Si potrebbe addirittura dire che in alcuni ambienti seminariali e accademici sono “diventati di moda“, in netto contrasto con il XIX secolo, quando non erano affatto “di moda” nemmeno nella maggior parte delle accademie teologiche ortodosse (a differenza dei migliori monasteri che conservarono sempre santi i loro ricordi e vissero attraverso i loro scritti).

Ma proprio questo fatto presenta un grande pericolo che occorre qui sottolineare. Il “diventare di moda” degli scritti spirituali più profondi non è affatto necessariamente una cosa positiva. In effetti, è molto meglio che i nomi di questi Padri rimangano del tutto sconosciuti piuttosto che siano semplicemente l’occupazione di studiosi razionalisti e “pazzi convertiti” che non traggono alcun beneficio spirituale da loro ma aumentano solo il loro insensato orgoglio di “conoscere meglio” riguardo loro più di chiunque altro o, peggio ancora, iniziano a seguire le istruzioni spirituali contenute nei loro scritti senza una preparazione sufficiente e senza alcuna guida spirituale. Tutto ciò, certo, non significa che chi ama la verità debba abbandonare la lettura dei Santi Padri; Dio non voglia! Ma significa che tutti noi – studiosi, monaci, o semplici laici – dobbiamo avvicinarci a questi Padri con il timore di Dio, con umiltà e con una grande sfiducia nella nostra saggezza e nel nostro giudizio. Ci avviciniamo a loro con lo scopo di imparare, e prima di tutto dobbiamo ammettere, dunque, che per questo motivo abbiamo bisogno di un insegnante. E gli insegnanti esistono: nei nostri tempi in cui gli Anziani portatori di Dio sono scomparsi, i nostri insegnanti devono essere quei Padri che, soprattutto nei tempi a noi vicini, ci hanno detto specificamente come leggere – e come non leggere – gli scritti ortodossi. sulla vita spirituale. Se lo stesso beato Paisius Velichkovsky, il compilatore della prima Filocalia slava, fu “preso da paura” quando apprese che tali libri sarebbero stati stampati e non più circolati sotto forma di manoscritti in alcuni pochi monasteri, allora quanto più dobbiamo avvicinarci a loro con timore e comprendere la causa della sua paura, affinché non si abbatta su di noi la catastrofe spirituale da lui prevista.

Il beato Paisius, nella sua lettera all’archimandrita Teodosio dell’Eremo di San Sofronio, [nota: dall’edizione di Optina della Vita e degli Scritti dell’anziano Paisius, pp. 265-267] scriveva: “Per quanto riguarda la pubblicazione a stampa dei libri patristici, sia in lingua greca che in lingua slava, sono colto da gioia e timore. Da gioia, perché non saranno consegnati all’oblio definitivo e gli zelatori potranno più facilmente acquisirli; da timore, perché sono spaventato e tremo per il fatto che vengano offerti, come se potessero essere venduti come gli altri libri, non solo ai monaci, ma anche a tutti i cristiani ortodossi, e per il fatto che questi ultimi, avendo studiato l’opera della preghiera mentale in modo autonomo, senza l’istruzione di coloro che sono esperti in essa, possano cadere nell’inganno, e per il fatto che a causa dell’inganno i vanitosi possano essere blasfemi contro quest’opera santa e irreprensibile, che è stata testimoniata da moltissimi grandi e Santi Padri … e che a causa delle blasfemie seguano dubbi sull’insegnamento dei nostri Padri portatori di Dio”. La pratica della Preghiera mentale di Gesù, continua il Beato Paisius, è possibile solo nelle condizioni di obbedienza monastica.

Pochi sono, a dire il vero, nei nostri ultimi tempi di debole lotta ascetica, che lottano per le vette della preghiera mentale (o addirittura sanno cosa potrebbe essere); ma gli avvertimenti del Beato Paisius e di altri Santi Padri valgono anche per le difficoltà minori di molti cristiani ortodossi oggi. Chiunque legga la Filocalia e altri scritti dei Santi Padri, e anche molte Vite di Santi, incontrerà passaggi sulla preghiera mentale, sulla visione divina, sulla divinizzazione e su altri stati spirituali elevati, ed è essenziale per il cristiano ortodosso sapere cosa dovrebbe pensare e sentire a riguardo.

Vediamo dunque cosa dicono i Santi Padri di questo, e del nostro approccio ai Santi Padri in generale.

Il Beato Macario Anziano di Optina (+ 1860) ritenne necessario scrivere uno speciale “Avvertimento a coloro che leggono libri patristici spirituali e desiderano praticare la Preghiera mentale di Gesù” [nota: nella raccolta Lettere ai monaci, Mosca, 1862, pp. 358-380 (in russo)]. Qui questo grande Padre quasi del nostro secolo ci dice chiaramente quale dovrebbe essere il nostro atteggiamento nei confronti di questi stati spirituali: «I santi e teofori Padri hanno scritto dei grandi doni spirituali non perché qualcuno si sforzi indiscriminatamente di riceverli, ma affinché coloro che non li hanno, sentendo parlare di doni e rivelazioni così eccelsi, ricevuti da coloro che ne furono degni, riconoscano la propria profonda infermità e grande insufficienza, e siano involontariamente inclini all’umiltà, che è più necessaria a chi cerca salvezza che tutte le altre opere e virtù.” Ancora, San Giovanni della Scala (VI secolo) scrive: “Come un povero, vedendo i tesori reali, tanto più riconosce la propria povertà; così anche lo spirito, leggendo i resoconti delle grandi imprese dei Santi Padri, involontariamente è tanto più umiliato nel suo modo di pensare” (Gradino 26,25). Pertanto, il nostro primo approccio agli scritti dei Santi Padri deve essere di umiltà.

Scrive ancora san Giovanni della Scala: «Ammirare le fatiche dei santi è cosa lodevole; emularli salva le anime; ma desiderare all’improvviso di divenire loro imitatori è insensato e impossibile» (Gradino 4,42). Sant’Isacco il Siro (VI secolo) insegna nella sua seconda Omelia (come riassunta dall’Anziano Macario di Optina, op. cit. , p .364): “Coloro che cercano nella preghiera dolci sensazioni spirituali con aspettativa, e soprattutto coloro che tendono prematuramente alla visione e alla contemplazione spirituale, cadono nell’inganno del nemico e nel regno delle tenebre e dell’oscurità della mente, essendo abbandonati dall’aiuto di Dio e consegnati ai demoni per scherno a causa della loro orgogliosa ricerca al di sopra della loro misura e del loro valore.” Dobbiamo quindi rivolgerci ai Santi Padri con l’umile intenzione di iniziare la vita spirituale dal gradino più basso e senza nemmeno sognare di raggiungere quegli stati spirituali elevati che sono totalmente al di là delle nostre capacità. San Nilo di Sora (+ 1508), grande Padre russo dei tempi più recenti, scrive nella sua Regola Monastica (cap. 2): «Che diremo di coloro che, nel loro corpo mortale, hanno gustato il cibo immortale, che sono stati trovati degni di ricevere in questa vita transitoria una parte delle gioie che ci attendono nella patria celeste?. .. Noi, gravati di molti peccati e preda di passioni, siamo indegni anche di udire tali parole. Tuttavia, riponendo la nostra speranza nella grazia di Dio, siamo incoraggiati a conservare nella nostra mente le parole delle Sacre Scritture, affinché possiamo almeno crescere nella consapevolezza del degrado in cui sguazziamo.”

Per aiutare il nostro umile intento di leggere i Santi Padri, dobbiamo iniziare con i libri patristici elementari, quelli che insegnano l'”ABC”. Un novizio di Gaza del VI secolo scrisse una volta al grande anziano chiaroveggente San Barsanufio, proprio nello spirito dell’inesperto studente ortodosso di oggi: “Ho dei libri dogmatici e quando li leggo sento che la mia mente si trasferisce dai pensieri appassionati alla contemplazione dei dogmi”. A questo il santo anziano rispose: “Non vorrei che ti occupassi di questi libri, perché esaltano la mente in alto; ma è meglio studiare le parole degli anziani che umiliano la mente in basso. Non ho detto questo per sminuire i libri dogmatici, ma vi do solo un consiglio, perché i cibi sono diversi”. (Domande e risposte, n. 544). Uno scopo importante di questa Patrologia sarà proprio quello di indicare quali libri patristici sono più adatti ai principianti e quali vanno lasciati in un secondo momento.

Ancora una volta diciamo che diversi libri patristici sulla vita spirituale sono adatti ai cristiani ortodossi nelle loro diverse condizioni di vita: ciò che è adatto soprattutto ai solitari non è direttamente applicabile ai monaci che vivono la vita comune; ciò che vale per i monaci in generale non avrà diretta rilevanza per i laici; e in ogni condizione il cibo spirituale adatto a chi ha una certa esperienza può risultare del tutto indigeribile per i principianti. Una volta che si è raggiunto un certo equilibrio nella vita spirituale mediante la pratica attiva dei comandamenti di Dio nell’ambito della disciplina della Chiesa ortodossa, con la lettura fruttuosa degli scritti più elementari dei Santi Padri e con la guida spirituale dei padri viventi, allora si può ricevere molto beneficio spirituale da tutti gli scritti dei Santi Padri, applicandoli alla propria condizione di vita. Il Vescovo Ignazio Brianchaninov ha scritto al rbiguardo: “Si è notato che i novizi non riescono mai ad adattare i libri alla loro condizione, ma sono invariabilmente attratti dalla tendenza del libro. Se un libro dà consigli sul silenzio e mostra l’abbondanza di frutti spirituali di chi è raccolto in un profondo silenzio, il principiante ha sempre un fortissimo desiderio di ritirarsi nella solitudine, in un deserto disabitato. Se un libro parla di obbedienza incondizionata sotto la direzione di un Padre portatore di Spirito, il principiante svilupperà inevitabilmente il desiderio della vita più severa nella completa sottomissione ad un Anziano. Dio non ha dato al nostro tempo nessuno di questi due modi di vita. (L’Arena , cap. 10). Ciò che il Vescovo Ignazio dice qui sui monaci si riferisce anche ai laici, tenendo conto delle diverse condizioni della vita laicale. Al termine di questa Introduzione verranno fatti commenti particolari riguardanti la lettura spirituale per i laici.

San Barsanufio indica in un’altra Risposta (n. 62) un’altra cosa molto importante per noi che ci avviciniamo ai Santi Padri in modo troppo accademico: «Chi ha cura della propria salvezza non dovrebbe affatto chiedere [agli Anziani, cioè leggere i libri patristici ] solo per acquisire la conoscenza, poiché la conoscenza gonfia (1 Cor 8,1), come dice l’Apostolo; ma è quanto mai opportuno interrogarsi sulle passioni e su come si deve vivere la propria vita, cioè come salvarsi; poiché questo è necessario e conduce alla salvezza. Pertanto, non bisogna leggere i Santi Padri per mera curiosità o come esercizio accademico, senza l’intenzione attiva di mettere in pratica ciò che insegnano, secondo il proprio livello spirituale. I “teologi” accademici moderni hanno dimostrato abbastanza chiaramente che è possibile avere molte informazioni astratte sui Santi Padri senza alcuna conoscenza spirituale. Di essi san Macario il Grande dice (Omelia 17,9): “Proprio come uno vestito di stracci da mendicante potrebbe vedersi nel sonno come un uomo ricco, ma svegliandosi dal sonno si vede di nuovo povero e nudo, così anche coloro che deliberano sulla vita spirituale sembrano parlare logicamente, ma poiché ciò di cui parlano non è verificato nella mente da alcun tipo di esperienza, potere e conferma, rimangono in una sorta di fantasia”.

Una prova per verificare se la nostra lettura dei Santi Padri sia accademica o reale è indicata da San Barsanufio nella sua risposta a un novizio che si sentiva altezzoso e orgoglioso quando parlava dei Santi Padri (Risposta n. 697): “Quando tu conversi sulla vita dei Santi Padri e sulle loro risposte, dovresti condannare te stesso, dicendo: Guai a me! Come posso parlare delle virtù dei Padri, mentre io stesso non ho acquisito nulla di simile e non ho fatto alcun progresso? E io vivo istruendo gli altri a loro vantaggio; come potrebbe non adempiersi in me la parola dell’Apostolo: Tu che insegni agli altri, non insegni a te stesso? ” (Rm 2,21). L’insegnamento dei Santi Padri deve essere di auto-rimprovero.

Infine, dobbiamo ricordare che lo scopo principale della lettura dei Santi Padri non è quello di darci una sorta di “godimento spirituale” o di confermarci nella nostra rettitudine o conoscenza superiore o stato “contemplativo”, ma esclusivamente di aiutarci nella pratica del sentiero attivo della virtù. Molti Santi Padri discutono della distinzione tra vita “attiva” e vita “contemplativa” (o, più propriamente, “noetica”), ed è bene qui sottolineare che non si tratta, come qualcuno potrebbe pensare, di una qualche artificiosa distinzione tra coloro che conducono una vita “ordinaria” di “Ortodossia esteriore” o di semplici “buone azioni”, e una vita “interiore” coltivata solo dai monaci o da qualche élite intellettuale; affatto. C’è solo una vita spirituale ortodossa, ed è vissuta da ogni lottatore ortodosso, sia monaco che laico, principiante o avanzato; “azione” o “pratica” (praxis in greco) è la via, e la “visione” (theoria) o “divinizzazione” è la fine. Quasi tutti gli scritti patristici si riferiscono alla vita dell’azione, non alla vita della visione; quando viene menzionata quest’ultima, è per ricordarci lo scopo delle nostre fatiche e delle nostre lotte, che in questa vita è gustato profondamente solo da alcuni dei grandi Santi, ma nella sua pienezza è conosciuto solo nell’era a venire. Anche gli scritti più elevati della Filocalia, come scrive il vescovo Teofane il Recluso nella prefazione dell’ultimo volume della Filocalia in lingua russa, “non hanno avuto in mente la vita noetica, ma quasi esclusivamente la vita attiva”.

Anche con questa introduzione, a dire il vero, il cristiano ortodosso che vive nel nostro secolo di conoscenza gonfiata non sfuggirà ad alcune delle trappole in agguato per chi desidera leggere i Santi Padri nel loro pieno significato e contesto ortodosso. Fermiamoci quindi qui, prima di iniziare la Patrologia vera e propria, ed esaminiamo brevemente alcuni degli errori che sono stati commessi dai lettori contemporanei dei Santi Padri, con l’intento di formarci un’idea ancora più chiara su come non leggere i Santi Padri . .

ENGLISH VERSION

The Holy Fathers of Orthodox Spirituality

Part II. How to Read the Holy Fathers

THE PRESENT PATROLOGY will present the Fathers of Orthodox spirituality;therefore, its scope and aims are rather different from the ordinary seminary course in Patrology. Our aim in these pages will be twofold: (1) To present the Orthodox theological foundation of spiritual life —the nature and goal of spiritual struggle, the Patristic view of human nature, the character of the activity of Divine grace and human effort, etc.; and (2) to give, the practical teaching on living this Orthodox spiritual life, with a characterization of the spiritual states, both good and bad, which one may encounter or pass through in the spiritual struggle. Thus, strictly dogmatic questions concerning the nature of God, the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation of the Son of God, the Procession of the Holy Spirit, and the like, will be touched on only as these are involved in questions of spiritual life; and many Holy Fathers whose writings deal principally with these dogmatic questions and which touch on questions of spiritual life only secondarily, as it were, will not be discussed at all. In a word, this will be primarily a study of the Fathers of the Philokalia, that collection of Orthodox spiritual writings which was made at the dawn of the contemporary age, just before the outbreak of the fierce Revolution in France whose final effects we are witnessing in our own days of atheist rule and anarchy.

In the present century there has been a noticeable increase of interest in the Philokalia and its Holy Fathers. In particular, the more recent Fathers such as St. Simeon the New Theologian, St. Gregory the Sinaite, and St. Gregory Palamas, have begun to be studied and a few of their writings translated and printed in English and other Western languages. One might even say that in some seminary and academic circles they have “come into fashion,” in sharp contrast to the 19th century, when they were not “in fashion” at all even in most Orthodox theological academies (as opposed to the best monasteries, which always preserved their memories as holy and lived by their writings).

But this very fact presents a great danger which must here be emphasized. The “coming into fashion” of the profoundest spiritual writings is by no means necessarily a good thing. In fact, it is far better that the names of these Fathers remain altogether unknown than that they be merely the occupation of rationalist scholars and “crazy converts” who derive no spiritual benefit from them but only increase their senseless pride at “knowing better” about them than anyone else, or—even worse—begin to follow the spiritual instructions in their writings without sufficient preparation and without any spiritual guidance. All of this, to be sure, does not mean that the lover of truth should abandon the reading of the Holy Fathers; God forbid! But it does mean that all of us—scholar, monk, or simple layman—must approach these Fathers with the fear of God, with humility, and with a great distrust of our own wisdom and judgment. We approach them in order to learn, and first of all we must admit that for this we require a teacher. And teachers do exist: in our times when the God-bearing Elders have vanished, our teachers must be those Fathers who, especially in the times close to us, have told us specifically how to read—and how not to read—the Orthodox writings on the spiritual life. If the Blessed Elder Paisius Velichkovsky himself, the compiler of the first Slavonic Philokalia, was “seized with fear” on learning that such books were to be printed and no longer circulated in manuscript form among some few monasteries, then how much the more must we approach them with fear and and understand the cause of his fear, lest there come upon us the spiritual catastrophe which he foresaw.

Blessed Paisius, in his letter to Archimandrite Theodosius of the St. Sophronius Hermitage,[1] wrote: “Concerning the publication in print of the Patristic books, both in the Greek and Slavonic languages, I am seized both with joy and fear. With joy, because they will not be given over to final oblivion, and zealots may the more easily acquire them; with fear, being frightened and trembling lest they be offered, as a thing which can be sold even like other books, not only to monks, but also to all Orthodox Christians, and lest these latter, having studied the work of mental prayer in a self-willed way, without instruction from those who are experienced in it, might fall into deception, and lest because of the deception the vain-minded might blaspheme against this holy and irreproachable work, which has been testified to by very many great Holy Fathers… and lest because of the blasphemies there follow doubt concerning the teaching of our God-bearing Fathers.” The practice of the mental Prayer of Jesus, Blessed Paisius continues, is possible only under the conditions of monastic obedience.

Few are they, to be sure, in our latter times of feeble ascetic struggle, who strive for the heights of mental prayer (or even know what this might be); but the warnings of Blessed Paisius and other Holy Fathers hold true also for the lesser struggles of many Orthodox Christians today. Anyone who reads the Philokalia and other writings of the Holy Fathers, and even many Lives of Saints, will encounter passages about mental prayer, about Divine vision, about deification, and about other exalted spiritual states, and it is essential for the Orthodox Christian to know what he should think and feel about these.

Let us, therefore, see what the Holy Fathers say of this, and of our approach to the Holy Fathers in general.

The Blessed Elder Macarius of Optina (+ 1860) found it necessary to write a special “Warning to those reading spiritual Patristic books and desiring to practice the mental Prayer of Jesus.” [2] Here this great Father almost of our own century tells us clearly what our attitude should be to these spiritual states: “The holy and God-bearing Fathers wrote about great spiritual gifts not so that anyone might strive indiscriminately to receive them, but so that those who do not have them, hearing about such exalted gifts and revelations which were received by those who were worthy, might acknowledge their own profound infirmity and great insufficiency, and might involuntarily be inclined to humility, which is more necessary for those seeking salvation than all other works and virtues.” Again, St. John of the Ladder (6th century) writes: “Just as a pauper, seeing the royal treasures, all the more acknowledges his own poverty; so also the spirit, reading the accounts of the great deeds of the Holy Fathers, involuntarily is all the more humbled in its way of thought” (Step 26:25). Thus, our first approach to the writings of the Holy Fathers must be one of humility.

Again, St. John of the Ladder writes: “To admire the labors of the Saints is praiseworthy; to emulate them is soul-saving; but to desire suddenly to become their imitators is senseless and impossible” (Step 4:42). St. Isaac the Syrian (6th century) teaches in his second Homily (as summarized by Elder Macarius of Optina, op. cit.,p. 364): “Those who seek in prayer sweet spiritual sensations with expectation, and especially those who strive prematurely for vision and spiritual contemplation, fall into the deception of the enemy and into the realm of darkness and the obscurity of the mind, being abandoned by the help of God and given over to demons for mockery because of their prideful seeking above their measure and worth.” Thus, we must come to the Holy Fathers with the humble intention of beginning the spiritual life at the lowest step,and not even dreaming of ourselves attaining those exalted spiritual states, which are totally beyond us. St. Nilus of Sora (+ 1508), a great Russian Father of more recent times, writes in his Monastic Rule (ch. 2), “What shall we say of those who, in their mortal body, have tasted immortal food, who have been found worthy to receive in this transitory life a portion of the joys that await us in our heavenly homeland?… We who are burdened with many sins and preyed upon by passions are unworthy even of hearing such words. Nevertheless, placing our hope in the grace of God, we are encouraged to keep the words of the holy writings in our minds, so that we may at least grow in awareness of the degradation in which we wallow.”

To aid our humble intention in reading the Holy Fathers, we must begin with the elementary Patristic books, those which teach the “ABCs.” A 6th-century novice of Gaza once wrote to the great clairvoyant Elder, St. Barsanuphius, much in the spirit of the inexperienced Orthodox student of today: “I have dogmatic books and when reading them I feel that my mind is transferred from passionate thoughts to the contemplation of dogmas.” To this the holy Elder replied: “I would not want you to be occupied with these books, because they exalt the mind on high; but it is better to study the words of the Elders which humble the mind downward. I have said this not in order to belittle the dogmatic books, but I only give you counsel; for foods are different.” (Questions and Answers, no. 544). An important purpose of this Patrology will be precisely to indicate which Patristic books are more suitable for beginners, and which should be left until later.

Again, different Patristic books on the spiritual life am suitable for Orthodox Christians in different conditions of life: that which is suitable especially for solitaries is not directly applicable to monks living the common life; that which applies to monks in general will not be directly relevant for laymen; and in every condition, the spiritual food which is suitable for those with some experience may be entirely indigestible for beginners. Once one has achieved a certain balance in spiritual life by means of active practice of God’s commandments within the discipline of the Orthodox Church, by fruitful reading of the more elementary writings of the Holy Fathers, and by spiritual guidance from living fathers—then one can receive much spiritual benefit from all the writings of the Holy Fathers, applying them to one’s own condition of life. Bishop Ignatius Brianchaninov has written concerning this: “It has been noticed that novices can never adapt books to their condition, but are invariably drawn by the tendency of the book. If a book gives counsels on silence and shows the abundance of spiritual fruits that are gathered in profound silence, the beginner invariably has the strongest desire to go off into solitude, to an uninhabited desert. If a book speaks of unconditional obedience under the direction of a Spirit-bearing Father, the beginner will inevitably develop a, desire for the strictest life in complete submission to an Elder. God has not given to our time either of these two ways of life. But the books of the Holy Fathers describing these states can influence a beginner so strongly that out of inexperience and ignorance he can easily decide to leave the place where he is living and where he has every convenience to work out his salvation and make spiritual progress by putting into practice the evangelical commandments, for an impossible dream of a perfect life pictured vividly and alluringly in his imagination.” Therefore, he concludes: “Do not trust your thoughts, opinions, dreams, impulses or inclinations, even though they offer you or put before you in an attractive guise the most holy monastic life” (The Arena, ch. 10). What Bishop Ignatius says here about monks refers also to laymen, with allowance made for the different conditions of lay life. Particular comments will be made at the end of this Introduction concerning spiritual reading for laymen.

St. Barsanuphius indicates in another Answer (no. 62) something else very important for us who approach the Holy Fathers much too academically: “One who is taking care for his salvation should not at all ask [the Elders, i.e., read Patristic books] for the acquiring only of knowledge, for knowledge puffeth up (I Cor. 8:1), as the Apostle says; but it is most fitting to ask about the passions and about how one should live one’s life, that is, how to be saved; for this is necessary, and leads to salvation.” Thus, one is not to read the Holy Fathers out of mere curiosity or as an academic exercise, without the active intention to practice what they teach, according to one’s spiritual level. Modern academic “theologians” have dearly enough demonstrated that it is possible to have much abstract information about the Holy Fathers without any spiritual knowledge at all. Of such ones St. Macarius the Great says (Homily 17:9): “Just as one clothed in beggarly garments might see himself in sleep as a rich man, but on waking from sleep again sees himself poor and naked, so also those who deliberate about the spiritual life seem to speak logically, but inasmuch as that of which they speak is not verified in the mind by any kind of experience, power, and confirmation, they remain in a kind of fantasy.”

One test of whether our reading of the Holy Fathers is academic or real is indicated by St. Barsanuphius in his answer to a novice who found that he became haughty and proud when speaking of the Holy Fathers (Answer no. 697): “When you converse about the life of the Holy Fathers and about their Answers, you should condemn yourself, saying: Woe is me! How can I speak of the virtues of the Fathers, while I myself have acquired nothing like that and have not advanced at all? And I live, instructing others for their benefit; how can there not be fulfilled in me the word of the Apostle: Thou that teachest another, teachest thou not thyself?“(Rom. 2:21.) Thus, one’s constant attitude toward the teaching of the Holy Fathers must be one of self-reproach.

Finally, we must remember that the whole purpose of reading the Holy Fathers is, not to give us some kind of “spiritual enjoyment” or confirm us in our own righteousness or superior knowledge or “contemplative” state, but solely to aid us in the practice of the active path of virtue. Many of the Holy Fathers discuss the distinction between the “active” and the “contemplative” (or, more properly, “noetic”) life, and it should be emphasized here that this does not refer, as some might think, to any artificial distinction between those leading the “ordinary” life of “outward Orthodoxy” or mere “good deeds,” and an “inward” life cultivated only by monastics or some intellectual elite; not at all. There is only one Orthodox spiritual life, and it is lived by every Orthodox struggler, whether monastic or layman, whether beginner or advanced; “action” or “practice” (praxis in Greek) is the way, and “Vision” (theoria)or “deification” is the end. Almost all the Patristic writings refer to the life of action, not the life of vision; when the latter is mentioned, it is to remind us of the goal of our labors and struggles, which in this life is tasted deeply only by a few of the great Saints, but in its fullness is known only in the age to come. Even the most exalted writings of the Philokalia, as Bishop Theophan the Recluse wrote in the preface of the final volume of the Russian-language Philokalia, “have had in view not the noetic, but almost exclusively the active life.”

Even with this introduction, to be sure, the Orthodox Christian living in our century of puffed-up knowledge will not escape some of the pitfalls lying in wait for one who wishes to read the Holy Fathers in their full Orthodox meaning and context. Therefore, let us stop here, before beginning the Patrology itself, and examine briefly some of the mistakes which have been made by contemporary readers of the Holy Fathers, with the intention of thereby forming a yet dearer notion of how not to read the Holy Fathers.

Endnotes

1. From the Optina Edition of the Life and Writings of Elder Paisius, pp, 265-267.

2. In his collected Letters to Monks, Moscow, 1862, pp. 358-380 (in Russian).

From The Orthodox Word, Vol. 11, No.1 (Jan.-Feb.., 1975), 35-41.